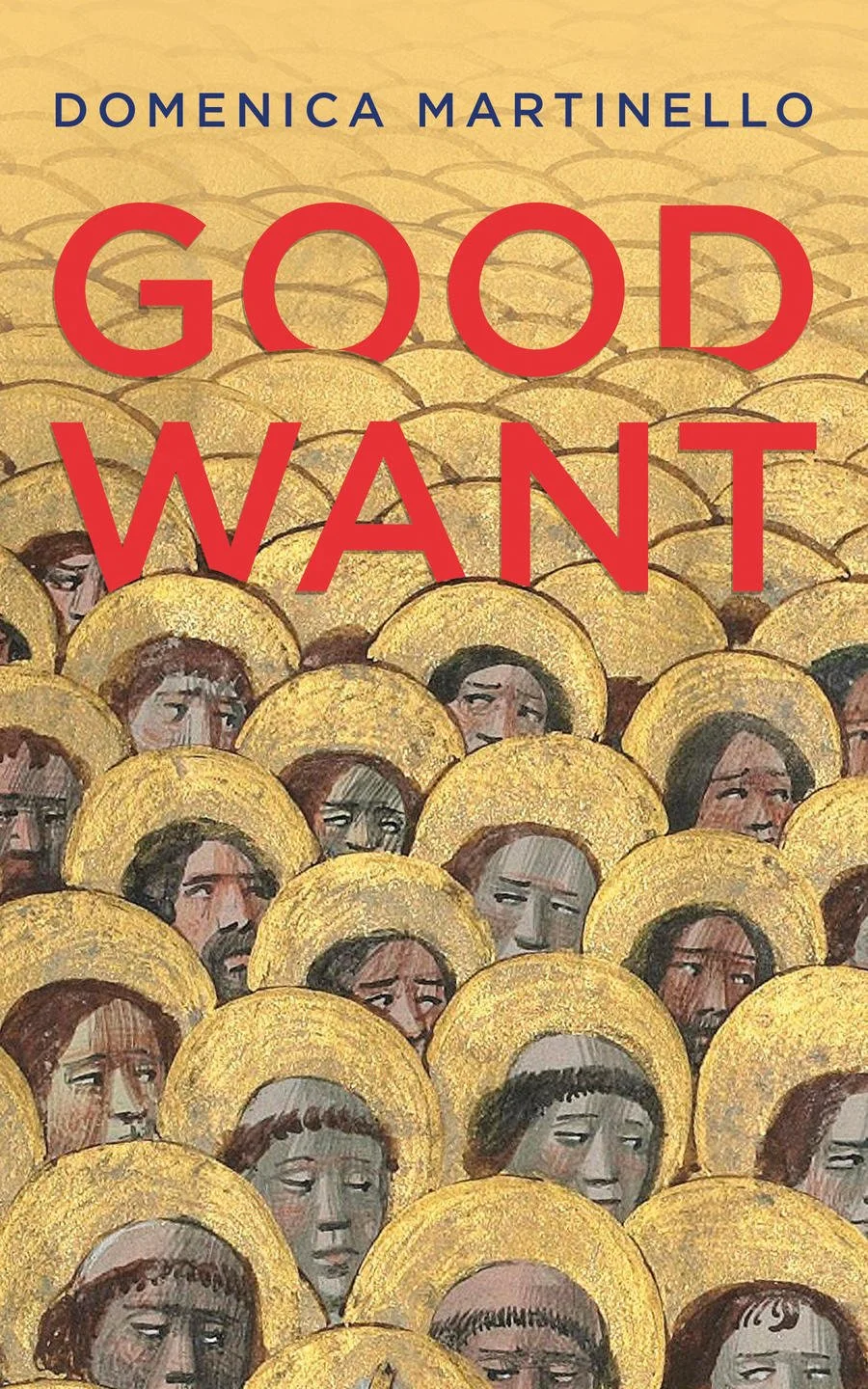

Review: Good Want by Domenica Martinello

Domenica Martinello’s second collection of poetry, Good Want (Coach House, 2024), is a hilarious, irreverent, stunning inquiry into the interplay between desire, class, faith, and goodness. Martinello brings her singular wit and wonder to bear on the stakes of desire, never losing sight of the soft, the sweet, the sunburnt, the strange.

On the back cover, Martinello asks, What if poetry and prayer are the same: intimate and inconclusive, hopeful and useless, a private communion that hooks you to the thrashing, imperfect world? The first poem in the book, “I Pray to Be Useful,” is a gorgeous (and useful) enactment of this comparison. The title alone raises its own set of questions—is the speaker praying that she is useful, or is she praying because prayer is useful, and therefore makes the one praying useful? And if prayer is useful, what is its use? Here, the speaker, kneeling at the foot of the oratory, prays “to want less.” But isn’t prayer an expression of what one wants? Isn’t prayer itself a kind of want? The speaker wants not to want. This is a prayer and a poem animated by contradiction, an ethos that Martinello cultivates in the impossible leap of this line break: “I atoned at each hot step / burning urgently like a secret / UTI.” The UTI is a secret hidden even to the poem itself, divulged to the reader at the exact right moment, erupting against the seriousness of the speaker’s atonement. In the end, neither prayer nor speaker has served their use: “I could not keep my gaze downcast, / humble, groundward. I could not fast.”

But what about the poem, what about its use? In “Asking For It,” we return to the comparison between poetry and prayer, their shared hope and futility:

Poetry often feels to me like

clicking the beads of a rosary.It’s not hurting anybody, I guess,

but that doesn’t make it virtuous.I’ve no faith in the abacus

or alphabet, a meek and uselesssonnet.

Domenica Martinello

Martinello deftly blends one into the other, figuring disillusioned believer as poet, fingers slipping between the syllables as though they were rosary beads. Even as the poem admits it’s “hoping to pull / a fast one. Doing nothing while wanting / the whole world to do more,” the reader keeps their faith—the reader still believes in this deceptively honest sonnet that proclaims its own passivity, that is bold in its meekness, relishes its hard-earned restraint.

I’m intrigued, too, by the title. What is goodness? What is want? What are the stakes of either? This collection is interested in both the moral and economic valences of wanting: “What does it mean, / to want good things?” What does it mean to “like something from nothing”? Good Want understands want as both a desire for something and a lack of it, a not having. In “All the Trimmings,” for example, lack multiples the want: “We even eat the garnish. Peel the plastic fruit in the plastic bowl. / Chip our teeth on ceramic lemons.” Even the words are good enough to eat, plosives of “Peel,” “plastic,” “bowl” popping open on the lips, saliva streaming forth for the sibilant “ceramic lemons.” we are told to “Waste not your wanting”; we “want more of everything.” it is this generous, all-encompassing want that allows the speaker to find the thrill of a garnish, that “sprig of noble nothing”—it is this same good want that “Stiffen[s] modestly to say, It’s nothing.”

We see something similar in “We Keep Sunlight in the Basement,” a poem that literalizes the idiom of a rainy day by imagining sunlight as a resource that can be slipped “into our purses, down our slips,” a panacea for problems as various as “hard callused feet” and “floods, famines, and disasters.” Sunlight is rich with symbolic associations: warmth, growth, cultivation, candour, and here it is also commodity, a thing only certain people get to feel, “a sign of life for people / who live in basements and cracks, / imagine juice out of powder, tide out / of detergent, wine out of water.” In the same way that the speaker’s family accumulates sunlight, the reader must also collect all that sunlight signals, all that it becomes. If “Amassing is a creative act,” Martinello asks the reader to partake in it, too, to gather up everything sunlight can hold. Martinello’s poems, like sunlight, make beautiful what is bare. They amass in order to give, out of a refusal “to show up empty-handed,” out of “faith in a world / in which someone will need / the small comfort of washing a dish.” Small comforts, these poems are everything we need.

There are several long poems throughout the book, as well, and each one is endlessly surprising and laugh-out-loud funny. Each of the book’s four sections concludes with these longer, deliciously voice-y poems (“In Bad Dreams,” “Sleep Is Trying to Tell Me Something,” “The Horses Eat Apples,” and “Casino World”), each building off of the previous one, transforming the same motifs, bound to each other with a string of six ellipses. After “In Bad Dreams,” where the speaker clocks in for her “evil night shift,” the speaker concludes in the next poem that sleep is trying to tell them “something about / all the badness of which I am capable.” In the bad dreams, the speaker forgets to feed pets; in her waking life, she even feeds the rabid squirrels. In “Sleep,” the speaker declares, “I will strike / little deals with myself not to lie / for no reason / and call that ‘having / integrity’”; in “The Horses,” the speaker “only lie[s] sometimes,” says “I always have my reasons.”

These poems have some of the funniest lines in the book. The speaker’s nonna, having “picked up a pigeon with her bare hands,” is described as “not above putting a live animal in her purse.” The poets will love this one: “Some years there are horse metaphors / even for those of us / with zero access to a horse.” And of the various figures populating the speaker’s head, my favourite has to be the elementary school teacher: “Her name is Nancy / Why can’t Nancy and everyone / just leave me the hell alone.”

The title poem, “Good Want,” a winner in The Malahat Review’s 2023 Long Poem Prize, is a tender, masterful, and heartwrenching poem that stretches to hold everyone and everything. It is a poem that doesn’t need to understand but will hold you anyway, where the past is not absent but can be smaller than it once was, a poem that knows just the right things to ask and not ask, that has the immense and unknowable power to forgive “everyone, everything”. Here, repetition is not stagnant or entrapping, but instead transforms, becoming the declaration of living things: “I am alive”. This is what Good Want gives us: a way “to say yes / and to keep on saying it”, the boundless want of being alive.