One Author’s Unusual Path to Immortality

Ninety years after his death, Fernando Pessoa is more alive than ever. His secret? Not finishing anything.

*

On a chilly November day in Lisbon, in the tree-lined bourgeois neighborhood of Campo de Ourique, a crowd of scholars gathered to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of a literary magazine that you’ve probably never heard of.

Athena, first published in October of 1924, has not become immortal due to an immediate and explosive impact on European culture at the time. (It had none.) Nor was Athena particularly successful; it ran only to 5 issues. And yet the conference room I had squeezed into—on the ground floor of the Casa Fernando Pessoa, a museum dedicated to Portugal’s most famous writer, housed in his former residence—was full.

The cover of the first issue of Athena, published in November 1924.

As I would later learn, scholars consider Athena still worth celebrating 100 years later because its pages were shared by four giants of Portuguese letters: Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis, Alberto Caeiro, and Athena’s editor, Fernando Pessoa. Their essays, poems, and translations spoke to each other across Athena’s five issues. They debated, introduced and critiqued each other. All of which sounds like literary business as usual, except for one important fact: they were all Fernando Pessoa.

You wouldn’t necessarily know this from eavesdropping on the conference, though. (Professor 1: “I think of Ricardo Reis as a Uranian.” Professor 2: “I don’t think Ricard Reis has anything Uranian about him whatsoever. Álvaro de Campos, however…”) But Pessoa’s compulsive penchant for creating other selves, and writing as them, is one of his defining characteristics.

As I wrote in a previous dispatch from the Casa, Fernando Pessoa was a man of many authors and few publications. During his lifetime, he published a single volume of poetry in Portuguese and a few pamphlets in English. At the same time, he managed to create dozens of personae, among them several Englishmen and a Frenchman (Pessoa was a polyglot who translated business correspondence to pay the bills), one woman, and one astrologer (Pessoa was, of course, a Gemini.)

For the most part, Pessoa created his alter egos in his own image, which is to say, they were writers, too. The three that came together in the pages of Athena—Ricardo Reis, Alberto Caeiro, and Alvaro de Campos—were the most prominent, although his English ones were also quite prolific writers. Under their names and his own, Pessoa produced 40 percent of the content of Athena, something that most of his collaborators were probably not aware of, scholars say. Pessoa was being generous, actually; earlier plans for the magazine had him writing 90 percent of the content.

But Athena was part of a much larger and ambitious work of fiction, I’ve come to understand—a work that, when the 90-year anniversary of Pessoa’s death rolls around this November, will still be very much in progress.

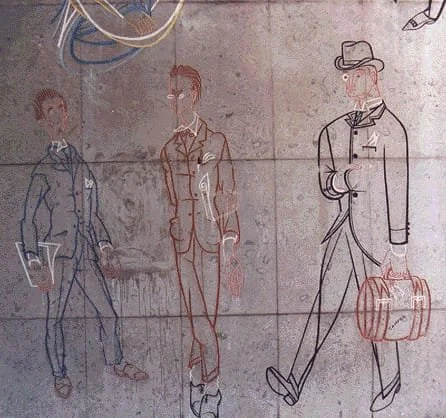

A mural at the University of Lisbon depicting Fernando Pessoa’s other identities, painted in 1958 by Almada Negreiros.

In 1928, after Athena was long gone, Pessoa finally revealed the true identities of Reis, de Campos, and Caeiro, in an article he titled “Bibliographic Table,” published in the magazine Presença (not his own magazine, for once.) He also revealed the intention behind them: “The works of these three poets form, as one says, a dramatic ensemble; and the intellectual interaction among the personalities, as well as their own personal relationships, are duly studied,” he wrote. “It is a drama in people, instead of in acts.”

He added that he planned to publish their biographies, horoscopes, and perhaps even photographs, although, as with most of Pessoa’s schemes, these plans were never realized. But Athena was the beginning.

“I think the importance of Athena is that the journal reveals in a clear way the drama in people,” Nuno Ribeiro, auxiliary researcher at the Institute for the Study of Literature and Tradition at the New University of Lisbon, told me. It was the day after the conference, and we were sitting at a table outside a hole-in-the-wall cafe a few steps from the Casa, enjoying the still mild November afternoon. He explained that, for scholars, Athena was not merely another short-lived modernist publication. It was the first stage upon which Pessoa acted out what was nearly a one-man show. Neither the audience, nor the real writers who joined him on the stage, knew that any of it was fiction.

Pessoa scholar Nuno Ribiero (right) presents his work at the Athena 100 Colloquium at the Casa Fernando Pessoa, alongside fellow scholar Fernando Cabral Martins (left).

In fact, Athena was only a small fragment of a much more ambitious plan: a massive publishing house-cum-multinational corporation called Olisipo. Olisipo’s vast range of activities were to include publishing translations of Portuguese works into other languages and translating foreign books into Portuguese (work that would be carried out by Pessoa and his various, multilingual alter egos); promoting Portuguese products abroad; and even the management of mining interests and sales of patents, just to mention a few. Not to mention developing inventions and board games. Pessoa’s plan included Olisipo offices located around the world.

“Of this vast plan, little was realized,” wrote Ana Maria Freitas in a summary of Olisipo on Modernismo.pt, a virtual archive dedicated to Pessoa’s milieu. After two years of operation in which a few books were published, Olisipo failed, in part because Pessoa had the courage in 1932 to publish a queer novel, Sodoma Divinizada, by Raul Leal.

Freitas added that, with Olisipo, Pessoa had “hoped to achieve an economic tranquility that would give him stability and allow him to dedicate himself fully to his work.”

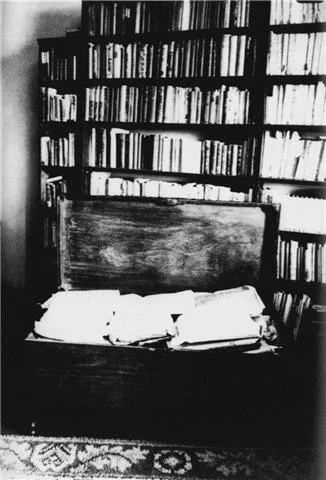

That stability never materialized. It wasn’t until 1934, the year before he died, that Pessoa published his first book in Portuguese, Mensagem. (Before that, he published four small books of poems English). He never married or had any children. Instead, he left behind a wooden chest full of about 25,000 pages of writing—on “loose sheets, notebook paper, stationery from the cafés he frequented, pages ripped from agendas or calendars, the backs of comic strips and flyers, book jackets, calling cards, envelopes, and the margins of manuscripts drafted a few days or a few years earlier,” according to Richard Zenith, one of Pessoa’s biographers.

And that is when Pessoa’s real life as an author began.

Pessoa’s trunk of unedited writings.

After Pessoa’s death, former collaborators and then scholars began sifting through the archive, editing and publishing those disorganized pages—in other words, finishing what Pessoa, in an act so characteristic of him, had left undone. In fact, Pessoa’s most famous work, The Book of Disquiet, a collection of about 500 pages written across 25 years and by multiple selves, was entirely gathered and edited posthumously, and, depending on the edition, its short chapters can appear in a different order.

The result, Ribeiro said, what Italian literary critic and author Umberto Eco calls an “open work,” an art form in which the structure itself is decided by the public, audience, or other actors who intervene with it. Other examples include Stephen Mallarmé’s Le Livre and Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “Klavierstuck XI,” written in 1956. The latter is a sequence of melodies that invites the performing pianist to choose the order of the melodies as well as the tempo and dynamics.

But it’s not just the Book of Disquiet that is an open work, Ribeiro said. It’s the whole archive. “Each editor is called to complete the work that Fernando Pessoa didn’t complete,” he said. And even Pessoa’s penchant to never finish anything has only served him: “Actually the result of these fragments and the multiplicity of projects, is, as Umberto Eco says, a living work, a work in movement.”

When Pessoa left these projects hanging, they were “attributed to a plurality of literary personalities entrusted with the task of signing those projects,” Ribeiro explained in a conference paper on the subject. Now it is a plurality of scholars who sign those projects, with their names and Pessoa’s on the title pages.

Which brought me to the question I was dying to ask Ribeiro, who has been working on Pessoa for 17 years, has published 40 books of Pessoa scholarship, including 20 books of writings edited from the archive, and was even married to another Pessoa researcher for a while:

Does he consider himself a heteronym of Fernando Pessoa?

“In a way, you work for him,” I said.

Ribeiro took my question with good humor. “Yes, I work for him,” he said. “And it’s curious that Fernando Pessoa, who had several struggles with money, is now financing people like me, for example. I have a contract with the university thanks to Fernando Pessoa.”

Later that week, scholars would gather at the Portuguese Academy of Sciences for another discussion of Athena. In February, the Casa hosted an International Pessoa Congress, and Ribeiro organized a coloquium. Pessoa’s Olisipo may have failed during Pessoa’s lifetime. But after his death, he did manage to build a long-lasting, multigenerational and multi-international corporation: Pessoa scholarship. He now has hundreds of people working for him, editing, translating, publishing, hobnobbing over pastel de nata and coffee in the lobby of a museum dedicated to him, debating his work at international congresses--in short, all the bustle and productivity on the grand scale Pessoa imagined but would never have been able to bring into being. Not to mention Portugal’s thriving industry of Pessoa-related souvenirs. For a souvenir merchant, a Pessoa tchotchke is the safest of bets—financial stability, indeed.

As we near the 90th anniversary of Pessoa’s death, Ribeiro estimates that about 50 percent of the archive is still to be published. Pessoans have plenty of open work still to live in, live off of, and define whole careers and identities by, probably for decades if not generations to come.

Photo by KP Vogell

Ribeiro and I parted ways, and I headed back to my apartment, hunching my shoulders now against the evening chill. Mulling over our conversation as I walked through Pessoa’s old neighborhood, I thought back on a detail I had noticed a few minutes into the first talk of the conference: Ribeiro and almost all of the male Pessoa scholars, at least the Portuguese ones, kind of looked alike. Or at the very least, they were dressed alike: soft sweaters in neutral colors, collared shirts, ill-fitting jeans, glasses. Most of them had dark hair and pale skin like Pessoa, and varying degrees of beard or moustache. And maybe my Gemini imagination was now running away with me, but any one of them wouldn’t have made a bad stand-in for Fernando Pessoa in a biopic.

In fact, I too was wearing a neutral-colored sweater, a collared shirt to make me look semi-respectable, and unfashionable jeans. I too have dark hair and glasses, and my olive skin turns a sickly pale green when I spend too much time indoors or only go out late at night. Having become fascinated by Pessoa three years before, I was now living, by happenstance, a few blocks from his house, walking at odd hours through the same streets that Pessoa himself must have traversed countless times. The sense of “desassossego,” or disquiet, that gives Pessoa’s most well known work its name, was as familiar to me as the half-destroyed leather jacket I wore everywhere. Sometimes, especially when I write, I feel real, vital, charged with energy; sometimes I feel half-real, like the heteronym of some other author who has neglected me for a while to write under another name; sometimes, not under the influence of alcohol like Pessoa, but after hours of aimless walking, I can start to float, and it feels like there is no “me” there at all.

Photo by KP Vogell

Athena, as the name implies, was also meant to bring Pessoa’s particular spiritual perspective, neo-paganism, to the masses. After centuries of hardcore Catholicism in Portugal, Pessoa sought a return from monotheism to a plurality of gods. Alberto Caeiro’s raw, apparently unselfconscious poetry, written in his house in the countryside of Pessoa’s imagination, embodied this organic aliveness. Given Pessoa’s many alter egos, it’s easy to see why paganism appealed to him, and he even went further than traditional paganism to argue for a plurality of the soul, Ribeiro told me.

But Pessoa’s heartfelt obsession with paganism was soon enough overwhelmed by a new passion: Jewish Kabbalah. “He says it was like an earthquake for his thoughts, and he was obliged to abandon paganism,” Ribeiro said.

One of the fundamental texts of Kabbalah is the Sefer Ha-Zohar, or the Book of Splendor. In his private library, Pessoa had a one-volume summary in English of the full 5-volume work. When Ribeiro opened the book, it teemed with Pessoa’s underlining. “One idea of Kabbalah, which haunted Fernando Pessoa and me as well, is that God is a man of even greater Gods,” Ribeiro said of his experience collecting Pessoa’s writings on Kabbalah. “Like, what man is to God, that God is like a man for another God.”

From my upbringing among Christians in America’s heartland, in God’s country, I remember often hearing God referred to as the Author. Pessoa, God-like, had created various men to carry out his will, including Caeiro, Reis, and de Campos. And if Pessoa’s author was God, that author might merely be the creation of yet another Author, farther removed, and so on. Pessoas all the way up, so to speak.

It does seem like a joke played on us by some kind of god, or the author winking at us from the page to let us know it’s all fiction: in Portuguese, “pessoa” means “person.”