With No Story to Save Me from Myself: A Conversation with Matthew Nienow

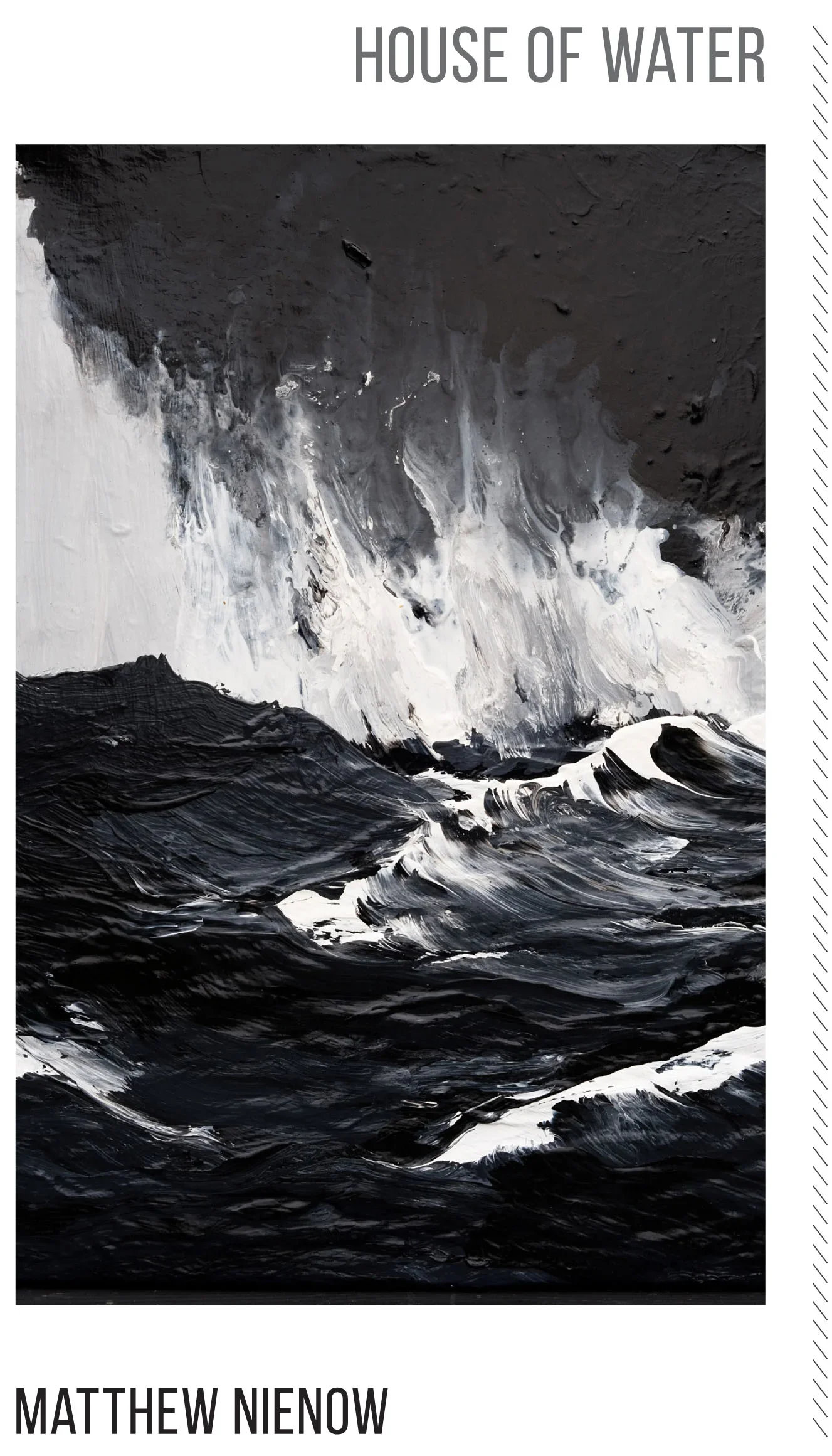

In his debut collection of poems, House of Water (Alice James Books, 2016), Matthew Nienow explored the ways in which the speaker’s work as a boat builder intersected with figurative and linguistic notions of poetic craft—that is, how one form of making might transform another. The book also movingly evokes the speaker’s experiences of fatherhood and family—themes that Nienow pursues further in his new collection, If Nothing (Alice James Books), published this spring. If Nothing is, however, a more somber and even more vulnerable book: it harrowingly recounts the speaker’s substance use disorder and mental illness, his recalcitrant road to recovery, and his lingering remorse over the ways in which his struggles have affected his roles as a partner and father. Throughout If Nothing, Nienonw’s poems balance inexorable guilt and the possibility of redemption—“I walked straight into the fire and took / my place among the ash,” he writes—while offering ephemeral moments of grace and tracing resiliencies of romantic and familial love. Recently, I spoke with Nienow via email about the genesis and journey of If Nothing. The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Michael Prior: Matthew, thank you so much for taking the time to talk about If Nothing. I was a few poems into the collection before I really understood the aptness of the title’s conditional phrasing. So much of the book grapples with regret, the way the unalterable past informs the uncertain present, especially when it comes to experiences of addiction and recovery. In “Dusk Loop,” the speaker heartbreakingly acknowledges that “some things cannot be repaired and must go on, into a kind of dusk / that seems somehow endless.” Yet If Nothing isn’t without hope or the possibility of grace (the collection ends with the speaker contemplating “how new / anyone forgiven / can become”). How did you conceptualize the role of poetry for you while writing around and through such harrowing experiences? If poetry can’t necessarily repair, or alter the past, what sorts of solace or hope might its making, its reading, offer for the present and future? How has your sense of what poetry can or can’t achieve for you, personally, been shaped by the process of writing this book?

Matthew Nienow: It’s been a strange and surreal experience putting this book out into the world, particularly as it is highlighting so much of what I did not know about the intersections between art-making and personal growth. Writing and living with these poems changed me. Though I began the work of getting sober and mending relationships off the page, in returning to the source of the wound again and again, I grew my ability and willingness to face uncomfortable and painful truths. This repeated, and careful attention to shame, regret, and grief in poems also clarified my interest in and commitment to being accountable as a man in my family and the wider world. Somehow, in my past work, there was always a border (even if imperceptible) between my day-to-day life and the making of poems, no matter how passionate I was about the subjects that called to me. At least with this book, that separation vanished, leaving me in new and untraveled territory, unsure how to proceed or articulate what I am seeing along the way. Though there is a place for poetry-writing-as-personal-therapy, it has always been important to me to make work that rises beyond my own small life toward something universal, regardless of whether the poems are beautiful or brutal, carefully crafted or wild and flawed. I guess I am amazed that making this book had such a substantial impact on my life while still (hopefully) arriving as a worthy entry in the long conversation between poets alive and dead and yet to come.

As the past cannot be changed, I find the resistance of neat endings hopeful—solace in the messiness of shining a light on regret and remorse with no expectation of a palatable and overly-simplified forgiveness. This has only become clear to me since the book’s release; during the years of drafting and revising, I was compelled by intuition and lacked the perspective only time and distance can provide. It turns out I was doing something essential for myself, but I couldn’t have said so honestly along the way. I only knew that poetry was a place for truth, and so I poured my life into the work as an antidote to years of hiding from myself.

I love what you say about the way the poems’ resistance to neat endings cultivates the potential for hope, as well as complex and painful truths. I also really admire what you say about writing toward or for something more than the merely therapeutic, even as poetry, is so often conceptualized in those terms. To clarify: reading the book, I never feel the poems are settling for therapeutic language or structures—their language is so much more beautifully interrogative and there’s never easy affirmation—the speaker rarely hears or realizes what would be most comforting.

In an essay you wrote for LitHub about the painful experiences that led to the genesis of If Nothing, you mention how,“[you] felt pulled to return to that pain, as though to heal a burn by standing by the fire.” I’m fascinated by that figure: the fire healing the burn (which makes me think of the recurring images of ash throughout the book). When writing If Nothing, how did you navigate the imperative to return to that pain—to address and redress it, to forge a new future for you and your family from it—and the need to also not become completely mired in it, or to recreate it in a way that ennobles the self (which I certainly don’t think the book does)?

The truth is that I was mired in it. I was, even as I tried to claim the immense good of many healthy changes, completely lost in shame, and guilt, and remorse. I tried to face it head on, and this became a part of how I grew up out of a younger and more fragile self into someone who could sit with so many memories it would be easier to forget….

I’m curious: formally, then, as a poet, when writing from this space of shame and guilt, how do you find, craft, connect the language that feels, well generative, and avoids self-aggrandizement for something quieter, truer, more piercing?

In my case, it took a fierce dedication to drafting and revising hundreds of poems in this thematic arena. Which is to say, I did write poems that were self-aggrandizing and that attempted to harness emotive power from an over-dramatized sob story. However, because I was a harsh and patient editor, and perhaps because I doubted whether any of the poems were any good, I did my best to make sure that all the poems that made it into the book really needed to be there and that they rose as close as possible to the unrealistically high standards I set for myself.

As you know, I also really admire your first collection, House of Water, which focuses on your training and work as a boatbuilder. Rituals and rhythms of work and attention deepen that book’s language in so many marvelous ways. There many rituals and rhythms (bodily, cognitive, and spiritual) in If Nothing, too, though in this newer work, these seem to often manifest in forms of prayer and apology (there is even a poem titled “Apologia”). I also noticed that many of the poems employ patterns of repetition, from a trio of ghazals (“Bookending the Day,” “Ghazal of Lost Years,” and “Ghazal of Air”) to the anaphoric constructions of poems like “On the Condition of Being Born,” “Raison D'être,” and “For Every Part that Shows.” I’d love to hear you speak a little about how the poems in If Nothing found their forms, their rhythms?

I am (and probably always will be) a poet of “the ear,” finding my way in poems through the sounds and textures of the language itself. At least initially, this is often the driving logic I follow intuitively toward a mix of surprise and clarity. From that place, I revise ruthlessly and obsessively. This holds true across the varied subjects my books have addressed.

During the time I was writing If Nothing, regret and remorse haunted me, returning throughout the day for years. This repetition, found in life, is mirrored in many of the poems, though I certainly wasn’t awake to this conceptualization until recently. I did know, however, that the book shouldn’t be too linear. Even with a general progression toward health, the need to apologize does not go away. Nor do the memories of earlier eras of active addiction. They still come to me, though I feel farther and farther away from the man I used to be. I’ll never be done growing, but I’m whole in a way that I wasn’t before getting sober and writing these poems.

Were there other poets, other books, other people’s words that helped you navigate the non-linearity of these experiences? Have you recognized that sort of progression, and distance between selves in other writers’ work in a way that has shaped your own?

I love this question and have become more curious about the distance between most writers and the work they publish. I think, aside from book contests that have a rapid turnaround, many poets endure a long period of writing and revising before submitting collections and waiting for responses. Even when someone gets lucky with a fast acceptance, publication is usually a couple of years out, which inherently creates a sense of distance between the self of the present and the selfhood (if applicable) of the speaker(s) in the published collection. As for specific books, I can’t say what specifically helped, but I remember reading and returning to books by Natalie Diaz, Eduardo C. Corral, Kaveh Akbar, Jericho Brown, Larry Levis, and Jack Gilbert, among others, during the years I was writing If Nothing. At the time, I was far more often reading individual poems in literary magazines and looking to encounter sparks of magic to ignite a sense of wonder I had grown distant from.